“Let me hear both sides”: Radiohead and political discourse

In recent years, political platforms endorsed by rock musicians been elevated to a prominent position in popular culture and in the psyches of mainstream Americans. Artists with uncompromising ideologies from Bob Dylan to John Lennon have been able to affect dramatic change in our nation’s political sphere through the impact of their music in culture. Doubtless one of the most influential artistic forces in music today, experimental rock band Radiohead has defied conventions and shattered expectations for almost two decades. With each new album, the English musicians have reinvented their sound and musical style, blurring the lines dividing alternative rock, electronica and jazz while exceeding fans’ every expectation. While their influence in the world of music is incontrovertible, Radiohead recently took a distinctly more political turn with 2003’s Hail to the Thief, which, predictably, offered the band’s perspective on the contemporary political climate in the United States. Taking cues from conventional political calls to action like Common Sense by Thomas Paine, Radiohead exercised and advanced traditional modes of political discourse in this country.

No time period in recent memory have been as politically divisive as the opening years of this new century. George W. Bush’s controversial and contested victory in the 2000 presidential election fragmented the country into polarized political extremes, followed soon thereafter by the psychological trauma and cultural panic that was September 11, 2001. This environment of political turmoil produced a great amount of political backlash, including near-universal polarization of mainstream perceptions of government organizations and leadership, ranging from resentment towards leadership officials and rebelliousness to virulent patriotism and widespread support of armed forces shipped overseas. This polarized culture produced some of the most emotionally-charged political activism in history, and is reminiscent of the pre-Revolution America within which Thomas Paine found himself: widespread popular discontentment with the system of authority, a culture itching for upheaval and revolution, and militaristic elements approaching their boiling points. But why should a bunch of postmodern rock stars like Radiohead be labeled our century’s equivalent of Thomas Paine?

The fact of the matter is, popular culture icons have supplanted historical geniuses in the minds of everyday Americans, and musicians like Thom Yorke, Radiohead’s lead vocalist and songwriter, have become the movers and shakers of our media-fueled society. Radiohead is considered a “concept album” band, each release embodying and working from within a central idea or overarching theme. For 1997’s OK Computer it was isolation and detachment in a technological society, for 2000’s Kid A it was mother nature’s reclamation of human civilization as a result of biotechnology and rampant consumerism,1 and for 2003’s Hail to the Thief it was political discontentment and ideological revolution. Anyone unfamiliar with the music of Radiohead would balk at these suggestions: is it even possible for such complex ideas to be properly expressed through a medium as low-brow as rock music?

In the time of Thomas Paine’s political activism, ideas were expressed almost exclusively in the form of political tracts, lengthy or, oftentimes the case for Paine’s essays, short enough to be printed upon a massively disseminated series of pamphlets. These articles could be as emotionally charged as any rock ballad today, with admonitions of pacifist countrymen like “challeng[ing] the warmest advocate for reconciliation to show a single advantage that this continent can reap by being connected to Great Britain” ,2 or arguments appealing to pathos like “the injuries and disadvantages which we sustain by that connection are without number, and our duty to mankind at large… instruct[s] us to renounce the alliance” .2 In truth, political pamphlets containing vitriolic language and an uncompromising commitment to change could be considered the angst-ridden “rock anthems” of the eighteenth century colonies.

A real modern example of the rock anthem, “2+2=5,” opener of Hail to the Thief—while obviously inspired more by Orwell’s dystopias than by the political treatises of Thomas Paine—nonetheless presents a great deal of politically-charged information right from the beginning. The album’s vocals begin with Yorke asking an anonymous authority mockingly, “Are you such a dreamer / To put the world to rights?” As the song progresses, however, his perspective becomes increasingly pessimistic, mentioning that “January has April’s showers / And two and two always makes a five,” casting doubt upon the administration’s rejection of climate change science by likening it to the Oceanic doublespeak in George Orwell’s classic 1984. Additionally, every track on the album is listed with its subtitle in parentheses, and the composition’s full name is “2+2=5 (The Lukewarm.),” suggesting that the intended audience of Yorke’s lyrics is political moderates and apathetic swing voters. Immediately after Thom mourns the environment’s being led to ruin comes the song’s volta,

It’s the devil’s way now

There is no way out

You can scream and you can shout

It is too late now

Because you have not been paying attention.

I fail to imagine a clearer call to arms than the frustrated lyrics here, as he repeats those last few words in a repetitive, deranged whine until the song’s conclusion.

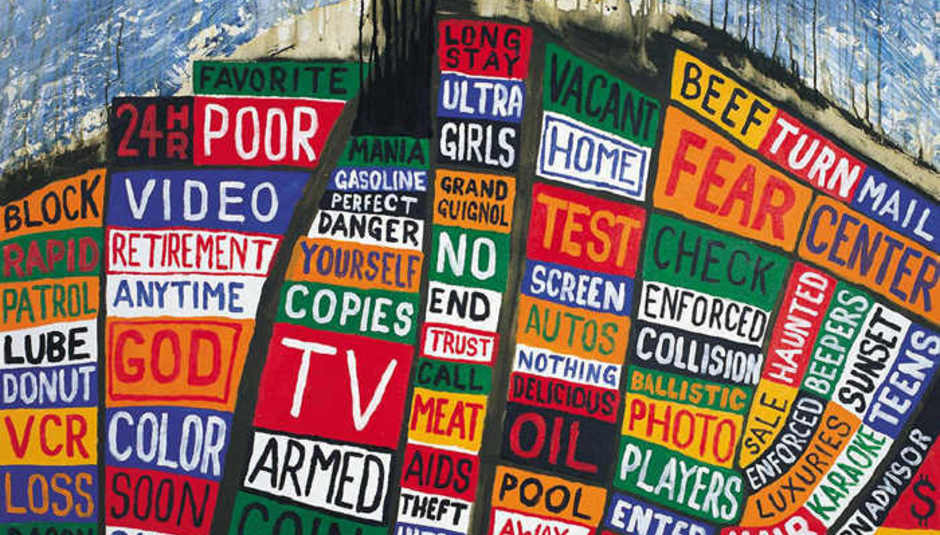

While other songs on Hail to the Thief are less activist and more personal to writer Yorke, who dedicated multiple tracks to his newborn son—specifically, “Sail to the Moon”—the primary focus of the work was to reflect the tumultuous political climate within which Yorke’s dystopian vision was composed. In a 2003 interview with NME magazine, Yorke provided a little more context for the album’s subject matter and stylistic elements, explaining that his listening to common buzzwords and phrases on the radio in the months following September 11, the War on Terrorism, and Afghanistan inspired the lyrics and imagery that makes the album so unique. “I was cutting these [phrases] out,” said Yorke, “and deliberately taking them out of context, so they’re like wallpaper,” a wallpaper with which he framed his apocalyptic reverie .3

Exploitation is an argument utilized by both Thomases Paine and Yorke, and each make convincing emotional appeals to readers’ or listeners’ pathos. For Paine, this exploitation came in the form of the British taking advantage of the American colonies, asking of those wishing to make peace with the overseas aggressors to “tell [him] whether you can hereafter love, honour, and faithfully serve the power that hath carried fire and sword into your land?”2 He also challenges pacifists to answer whether they “can still pass the violations over… hath your house been burnt? Hath your property been destroyed before your face? Are your wife and children destitute of a bed to lie on, or bread to live on?” These are all strong emotional appeals designed to rile a defensive aggression in readers, and to inspire them to reject the system of governance which had imposed such perceived injustices upon them.

In the case of Radiohead, exploitation of the working class at the hands of the capitalist machine is the subject of “We Suck Young Blood (Your Time Is Up.),” a nightmarish piano ballad which could define the album’s distinctive sound. Between handclaps and haunting backup vocals Yorke asks of potential laborers,

Are you hungry?

Are you sick?

Are you begging for a break? […]

Are you strung up by the wrists?

We want the young blood

Here he casts monopolizing corporations as vampirish monsters preying on the weak and disadvantaged.4 Thom’s distinctive falsetto wailing continues for another five minutes, interlaced with intense piano crescendos and a cappella backup vocals. The result is an effective metaphor relating real capitalism with a terrifying horror film where controlling vampires exploit the dependent elements of society, producing a memorable and visceral image in listeners’ minds.

Yorke, in the spirit of Paine, uses his art form to affect serious political change in contemporary society, utilizing similar rhetoric and presenting traditional arguments in a nontraditional and atypical media. Although separated by centuries and for the most part ignorant of one another, one cannot help but imagine that both Thomases would have gotten along famously, as both of them encouraged their cultures to, as Paine intones on page 997, “oppose not only the tyranny but the tyrant, stand forth! […] and prepare an asylum for mankind.”

-

Tate, Joseph. “Radiohead’s Anti-videos: Works of Art in the Age of Electronic Reproduction.” Postmodern Culture 12.3 (2002). Postmodern Culture. Web. 21 Oct. 2009. ↩

-

Paine, Thomas. “From Common Sense” Heath Anthology of American Literature. 6th ed. Vol. A. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2009. 992-7. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

NME Magazine. 3 May 2003: 27. Print. ↩

-

Tate, Joseph. “We (Capitalists) Suck Young Blood.” Radiohead and Philosophy. Ed. Brandon W. Forbes and George A. Reisch. Chicago, IL: Open Court, 2009. 111-21. ↩