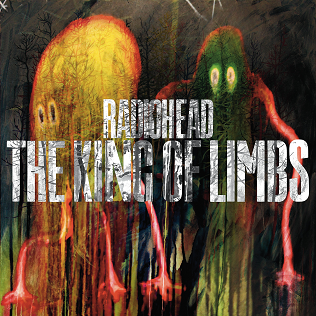

The water’s clear and innocent: Radiohead’s King of Limbs

Radiohead devotees are an interesting bunch. Since—along with millions of other fanatics the world over—my fandom of the Oxford experimental band borders on religious devotion, I was obviously ecstatic last week when the group announced the release of their eighth studio album, The King of Limbs. Being the followup to their 2007 album In Rainbows—which the popular media seems more inclined to remember for its pay-what-you-like distribution model than as a genuinely impressive artistic output—it’s easy to predict that no album due out in 2011 will prove as anticipated or as divisive as Radiohead’s latest. A band famous for routinely changing their sound from album to album, from grunge-era roots on 1994‘s The Bends to abstract and electronic epics like OK Computer and Kid A in 1997 and 2000 respectively, it was no surprise that this new album sounded rather different than anything the band had produced before. But despite its jarring electronic loops, computerized drums and disjointed, haunting ballads, The King of Limbs retained that ineffable quality that makes Radiohead so unique among their contemporaries—an emotional center as powerful and resonant as the highest points of “Fake Plastic Trees” some 15 years ago.

The 8-track opus was available for download a full day earlier than advertised, and I took the first available opportunity to plop myself down and listen it through. Millions of others undoubtedly did the same, and scores of them abandoned hope at track 4. But I soldiered on, listening from start to finish a half-dozen times that first night and some 45 times over the week since. Any Radiohead fan knows that, unlike their accessible Lady Gaga contemporaries, their work requires a bit of effort to penetrate—who among us would have thought that a song as discordant and amebic as Kid A’s “Everything In Its Right Place” would one day be listed among our favorites?

That being said, I’d be misleading you if I pretended I wasn’t disappointed. Some four years of Radiohead’s silence finally came to a close with a meager 8 tracks of electronic loops, more reminiscent of frontman Thom Yorke’s 2006 solo album The Eraser than anything. How could we have waited this long for this? For “Feral,” the almost-entirely instrumental series of bloops and digitally-altered falsettos draped over an impossible number of drum beats? For “Codex,” the despicably-titled shameless rehashing of 2001‘s “Pyramid Song,” imagery and all? Was Thom’s jerky dancing in the “Lotus Flower” video really the new image of Radiohead?

From an accessibility standpoint, the first half of the album was difficult to say the least. Between the erratic dissolution of drum beats in album opener “Bloom” and the repetitive looping of computer-bourne percussion in “Morning Mr. Magpie”—itself, might I add, a modernized version of a largely acoustic track from the Hail To The Thief era—I had a bad feeling about where the album was going. Promising tracks like “Little By Little” with its whispered lyrics like “you are such a tease and I’m such a flirt,” and single “Lotus Flower” seemed drowned in this electronic swamp wherein robotic drum kits did battle with robotic bass lines, and the acoustic ballads “Codex” and “Give Up The Ghost” in the latter half of the album felt woefully out of place. After my first listen through, I was nauseous. Was this even better than Pablo Honey?

After a few more listens, however, the realization began dawning on me: those loops and layers weren’t random, weren’t happenstance. Each song was a densely leveled and complex sort of house of cards (to use Radiohead’s own canon as imagery), a kind of puzzle, a maze for listeners to explore. And at the end, even on frustrating tracks like “Feral,” there is a payoff—Radiohead yet lives. Much like the Amnesiac, counterpart and counterpoint to Kid A, seemed overwhelming when it first graced ears in 2001, their latest opus would require a great deal of exposure to fully appreciate. Hidden in the abstraction “Feral” was a bass-y sort of groove, lost in “Give Up The Ghost” is the same sort of introspection we’ve come to love from Radiohead.

Just as OK Computer told of detachment and alienation in a technological society, The King of Limbs in a way depicts losing, and thereby finding, one’s self in the wilderness. Recorded near and named for one of the oldest trees in the world, a forest vibe can be noticed throughout the record, but nowhere more prominently than in the birdcalls between its most moving sixth and seventh tracks. The former, might I add, while being a close cousin to “Pyramid Song” before it, is so strong for many of the same reasons—the water imagery, the theme of complete release of responsibility, of ego. From “nothing to fear and nothing to doubt” to “you’ve done nothing wrong,” the moral is the same. This is a Radiohead song that will be remembered, even after their next few albums prove just as polarizing.

But the target of The King of Limbs is just that: polarization. Whereas 2007’s In Rainbows, much like the title implies, was colorful and lively (even its ballads were in “red-blue-green”), Limbs feels lifeless, almost drained of color. It’s a polar album, a response to and reversal of the pseudo-optimism that made In Rainbows so accessible and landed Radiohead a performance slot on that year’s Grammy awards. They updated their sound, but their message remains, their themes of isolation and detachment remain, and their quality remains. Despite its detractors, The King of Limbs earns its place among Radiohead’s pantheon.

In the album’s ultimate track, “Separator,” Thom offers a prophetic kind of promise to Radiohead fans—“If you think this is over, then you’re wrong.”