Tablet wars: how iPad is lapping the industry

How Apple won the everyman

I’m not one to offer blanket statements heralding the “end of traditional media” or label a product the “savior of the newspaper industry.” When the iPad was released less than a year ago, other people said these things, and more, for me. I’ve never claimed that the iPad would alter our realities, but I’ve seen it much as I see the iPhone: a game-changer for the consumer technology industry.

When the iPhone came onto the scene in 2007, journalists were quick to their conclusions about it. The “Jesus phone” became a popular moniker on technology blogs, indicative of its revolutionary place in our cultural consciousness. And while the iPhone was the first of its kind, a true pocket computer with a sharp design to boot, after a year or so there was very little that remained unique about it. Competitors like Motorola and HTC released devices with all the same capabilities, and the Android OS they ran soon kept pace with iOS’s steady development. Some would say that the modern competitors to the iPhone are superior in a number of ways, and some of their advantages—dual-core processors, for example—are empirically provable.

And yet, the media and national consensus maintains that the iPhone is the “only phone that matters,” and Apple’s innovations overshadow similar strides made by rivals. For years, no consumer product has received as much media attention as the iPhone—that is, until the iPad.

The slate was a natural extension of the iOS platform, offering a new form factor reminiscent in some ways of its MacBook cousins. The device gained traction with Apple’s preexisting App Store, and received a significant boost last fall with iOS 4’s new features. Again, what was significant about the iPad weren’t its features or technical specifications—within months, rivals had dreamt up new ways to compete. What mattered was that the iPad was first of its kind, and Apple’s head start allowed them to define the race before their competitors even realized they were running in it.

The question remains: why have these iOS devices been able to gain so much traction, even when competitors are beginning to offer comparable alternatives? Why does the iPad retain such a dominant market share, and why does it appear this trend will continue for years to come?

Gyrating silhouettes and market share

By 2001, the iPod wasn’t the first popular digital music player on the market, and its feature set was a disappointment to some. However, through their unique distribution channels, advertising and consistent addition of new features and form factors, Apple managed to secure its place as the ubiquitous and insurmountable gadget of the decade. Competitors like Microsoft’s Zune and Creative Zen were unable to achieve the level of consciousness penetration Apple could, and were doomed to having their products described to laypeople as “similar to an iPod.”

In 2007, with iPod nanos and shuffles added to the fray, Apple’s omnipotent flagship product gained a neighbor, the iPhone. The automatic brand recognition launched the iPhone into mainstream news immediately, not to mention its novelty considering a landscape populated by LG Chocolates and BlackBerries. Nothing like the iPhone had ever been seen before, and soon much of the smartphone industry’s products could be described as being “like an iPhone”—and were.

The importance here is not that the iPod and iPhone were the best products available. The debate between Android, iOS and now Windows Phone 7 is irrelevant to the point I aim to get across—regardless of what came before or after them, it cannot be denied that both Apple’s iPod and iPhone came to define the market. Everything before them was considered a prototype, everything that followed an imitator.

In much the same way, the iPad’s early entrance onto the scene allowed it to set the bar exactly where Apple wanted it, to frame the debate before it had even begun. By limiting the device’s feature set and with an affordable price point competitors would be hard-pressed to match, Apple set the foundations for their third dynasty in the mobile computing realm. With the aid of media coverage and rock-solid advertising, the iPad skyrocketed to national prominence and sold some 14 million units in its debut year.

A litmus test I like to use to measure a gadget’s penetration into the national consciousness is whether my grandparents—admittedly, relatively modern folk in their own right—are familiar with it. When asked about the Samsung Galaxy Tab or Motorola Xoom, my family members tend to shrug their shoulders and admit their unfamiliarity.

As for the iPad? They bought one.

Platform 60,000 & ¾

Another interesting perspective at the outset of this tablet war is to consider is the role of the operating system in determining advertising and market share. There has long existed a dichotomy in consumer electronics between those companies who sell exclusively software or exclusively hardware and those companies who sell both. Your typical PC was manufactured by HP or Dell and runs one of the many flavors of Windows, the hardware and software designed by different companies. As for Apple machines, both the Mac and the Mac OS were designed by engineers at the same firm, which some would argue ensures compatibility and improves user experience.

Interestingly, the same dichotomy has now extended to mobile computers. Whereas Apple designs both iPhone/iPad and iOS, the new slew of competitors run Google’s Android OS and are manufactured by HTC, Motorola, Samsung, or others. All of these products are equally likely to be fantastic for users in their own ways, but this departure in development complicates advertising in an interesting way.

Commercials for the Motorola Droid line or any of the innumerable HTC variations tout separately the merits of the device’s hardware and the Android software—they focus on the processor speed and add that it runs Android, or highlight how many megapixels their cameras have and name-drop Google. Customers looking to buy a Droid X or the HTC Incredible are aware of the Android operating system and its inclusion on the phone, perhaps because these devices are more popular with the tech-savvy. Android is a key selling point for these devices, and you’ll see most promotional material reading something along the lines of “The Manufacturer Phone-Name—running Google’s Android.” From the Motorola Xoom promotional site:

The MOTOROLA XOOM tablet has a super-fast dual-core processor and Android 3.0 (Honeycomb)—powerful Google software developed specifically for tablets. It features front and rear-facing cameras, a camcorder and Adobe® Flash® Player, all on a 10.1-inch widescreen HD display.

But for Apple, the advertising is decidedly different. Their commercials show the device and its software working in tandem, and little attention is paid to the technical ramifications. You’d be hard-pressed to find an iPhone or iPad ad that mentions the A4 processor’s speed—hell, you’d be hard-pressed to find a consumer ad that mentions the A4. For Apple, there is no separation between the iPhone and its software; iOS is as much a part of the product as its faulty antenna.

This contrast remains true in the new age of iPads and Android-based tablet competitors (the exception to this rule, of course, is Palm, who created both their hardware and the fantastic webOS until recently acquired by HP. It will be interesting to see what the focus is in advertising for the next Pre and touchPad). I promise you, over the next few months you’ll hear the words “Honeycomb” and “Snapdragon” in advertisements more times than you can count—but I doubt you’ll hear A5 or iOS uttered once in commercials. An example of Android tablet advertising:

By not suggesting to customers that they might divorce the software and hardware, Apple is leading them to the conclusion that every element of the iPhone or iPad is an intrinsic factor of the overall product, that every component is merely part of a whole, rather than a selling point. It just works. They focus not on the statistics but on the experience—from Apple’s front page for the iPad:

iPad: A magical and revolutionary product at an unbelievable price. Starting at $499.

The difference, perhaps, is that for most users iOS feels like a natural extension of the hardware—being designed by the same company, the experience is seamless. In addition, the wildly popular App Store featuring some 60,000 apps for the iPad alone is integrated natively into the OS. Most users don’t even think much of the lucrative machine on their home screens—they just watch for the occasional update to Angry Birds.

On the Android platform, this seamless experience is relatively unheard of. Between the multiple old versions of Android being sold on brand-new phones today, the manufacturer customizations to the GUI like MOTOBLUR and HTC Sense, and the dozens of form factors and capabilities on various Android devices, installing an app as simple as Twitter can become a headache. Does it support my version of Android? Does it support my screen resolution? Does my carrier allow it? These are questions that iPhone and iPad users never have to contemplate. Hell, they probably don’t even realize such limitations could exist.

And while Apple’s “walled garden” isn’t perfect for developers, from a user’s perspective connecting with apps and content has never been easier. Again, purchasing songs from the iOS iTunes Store and downloading Instagram from the App Store are such simple operations that even a child can perform them, and they’re understood by consumers to be just another feature of iPads and iPhones.

Until the manufacturers of Android devices can convince users that using their products are seamless, integrated, and painless experiences—experiences that don’t require an understanding of the technobabble so many mainstream consumers are so phobic of—the everyman will never be more interested in something like the Motorola Xoom with Google Android Honeycomb. Until they convince consumers that using their products is easy, intuitive, and even fun, they’ll never be more popular than Apple’s iPad.

And they’ll have a difficult time convincing anyone of that, because it’s simply not true.

The year of iPad 2

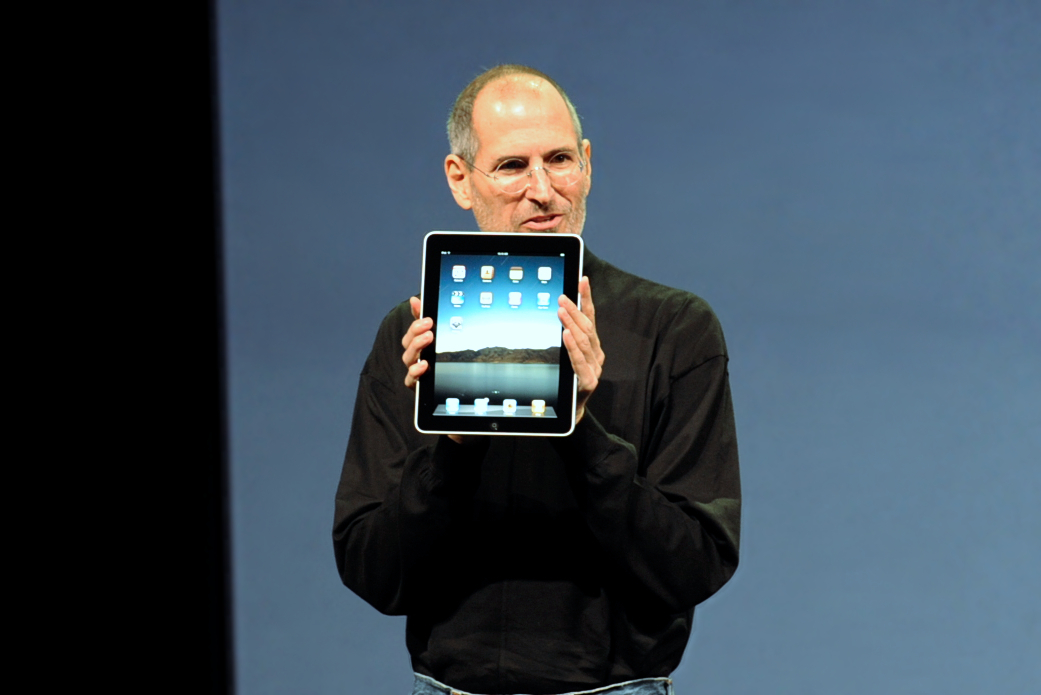

Last Thursday, Apple introduced the second generation of their wildly successful iPad to an overall positive reception from the popular media. Boasting a new feature set and form factor, surprise introducer Steve Jobs deemed it a “post-PC device” in the same vein as the iPhone and iPod before it. Claiming that 2010 had proven the “year of the iPad,” he said he wanted to prevent competitors from controlling the rhetoric in 2011. Not only has iPad 2 silenced competitors, it seems to have routed them entirely.

The capabilities of iPad 1 were subject to scrutiny and criticism from the technology industry—no cameras? No Flash player? These were probably intentional omissions on Apple’s part—to keep down prices and improve battery life, respectively—but became targets of the new slew of competitors that came in the following months. Nearly every one of the new “iPad-killers” announced over the past few months—HP’s TouchPad, BlackBerry’s PlayBook, Samsung’s Galaxy Tab and Motorola’s Xoom—have featured at least one camera and Flash compatibility (in the case of the Xoom, compatibility due at some point in the future). They took aim at what they perceived to be Apple’s weak points on the iPad, and framed their advertising around what they considered advantages.

Interestingly, Apple will have released two generations of their tablet before some competitors have released their first—the PlayBook’s release calendar is constantly changing and the TouchPad is due in “summer.” Worse yet, the claimed advantages of these yet-to-be-released competitors, including the overlooked cameras and dual-core processing, have been rendered obsolete by the iPad 2 which features both. They’ll be competing with last year’s product while the current generation becomes another blockbuster success. And even their best efforts will fall short—even with perceived advantages over 2010‘s iPad—because of their price points. $799 for a tablet with significantly fewer apps than the $499 iPad?

And “significantly” is no understatement: the iPad runs 65,000 apps designed specifically for its resolution and hardware capabilities in addition to the hundreds of thousands of preexisting iPhone apps while Honeycomb devices are lucky to find even 100 apps optimized for them. Coupled with the media zeitgeist sure to follow the iPad 2 launch, it’s conceivable that Apple will continue to own the fledgling tablet market for years to come.