What if Apple replaced all its Mac apps with Catalyst?

Of course they shouldn’t do it. But what if they did? What features would they leave behind, or bring to iOS? Where does it make sense for them to do this, and where would it never work?

When this post was originally published in 2019, Marzipan was the rumored codename for the framework that ultimately became Mac Catalyst. For clarity, I’ve updated references to “Marzipan” to “Catalyst” throughout the article.

Apple’s announcement at WWDC 2018 that four new apps—News, Voice Memos, Home, and Stocks—were making their way from iOS to macOS was a welcome surprise, and signaled a major change in strategy for the steward of some of the world’s most popular and important platforms. Rather than building distinct codebases for each of its properties across each of its platforms (and expecting third-party developers to do the same), Apple was beginning to migrate UIKit, the developer framework for iOS apps, to macOS. Forget iTunes for Windows, this was actually hell freezing over.

Developers investigated macOS 10.14 Mojave and learned a great deal about how these apps worked, and what it indicated for the future. Evidence suggested that this internal project was codenamed Marzipan, and some of the system files that OS sleuths uncovered confirmed it. There were, and are, a ton of hiccups with the UIKit apps as they stand today—suffice it to say they’re decidedly not Mac-like in many respects. But with Microsoft and Google both making it easier to develop cross-platform apps, or run mobile apps in a desktop context, Apple needed to do something to make its Mac App Store and macOS ecosystem feel as much of a first-class citizen as iOS.

From a strategic standpoint, this makes a world of sense for today’s Apple. Rather than spreading its developer resources thin by creating both an AppKit version and a UIKit version of any of its new ideas, they’d be able to leverage the same code across both platforms with greatly reduced effort. One app for Apple News and its new magazine subscription service. One app for Apple TV+ when it launches. Presumably one app for each new game published under the Apple Arcade program and created by third-party developers, meaning their content can be enjoyed across iOS, macOS, and tvOS from day one. This isn’t just a developer curiosity, it’s good business.

Developers will no longer need to rebuild their app to publish it in the Mac App Store, meaning a universe of great iOS apps might soon be available for download on your MacBook. Win, win, win.

But this approach also leaves a ton of questions. What happens to established AppKit apps on the Mac, especially those that are getting kind of long in the tooth? Should we expect Apple to revamp them with Mac-first features, or replace them with their iOS brethren in a future release?

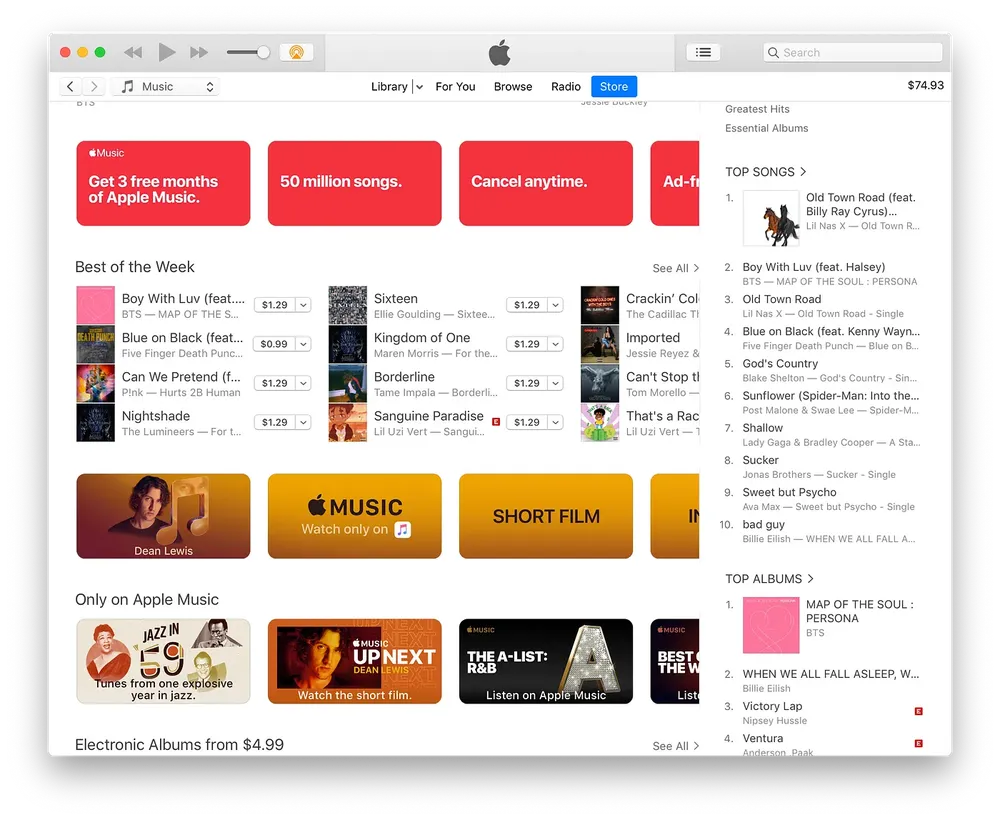

This month, iOS developer celebrities Steve Troughton-Smith and Guilherme Rambo uncovered evidence that Apple intended to replace iTunes with a suite of new Catalyst apps for Podcasts, Music, and TV in this fall’s release of macOS 10.15. According to the pair, Apple Books for macOS would also be replaced by a Catalyst port of its iOS app, which was redesigned in version 11.3. This is the long-heralded break-up of iTunes, which Mac enthusiasts have been clamoring about for more than a decade. But at what cost?

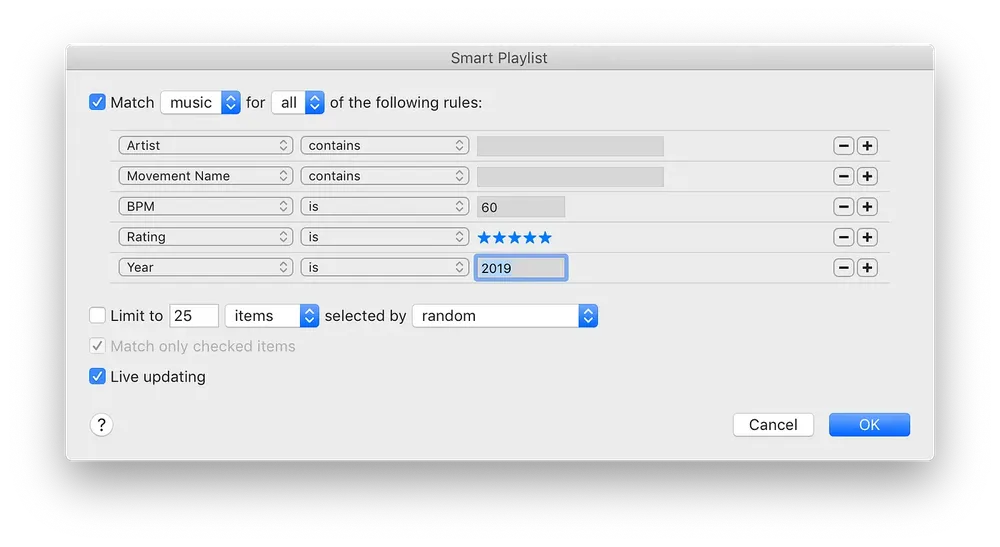

iTunes on the Mac facilitates a ton of legacy functionality and power-user features that can’t be squared with the current versions of Music, TV, and Podcasts for iOS. Macworld shared a helpful overview of what features might be left behind in the trade, including iOS and iPod device management, Smart Playlists, music file metadata management, and Genius among them. Many of these features likely aren’t important to Apple’s strategy looking ahead, and there might be a transition period where iTunes remains available to alleviate the functional gap, but this got me thinking.

What would happen if Apple replaced every macOS system app with a Catalyst equivalent?

Look, I get it. This is obviously a nightmare scenario for many Mac diehards, myself included, and I honestly don’t think anyone expects this to really happen, even on an infinite timescale. But it’s an interesting thought exercise: what are the functional gaps between macOS apps and iOS apps today? How easy would it be to reconcile them, making both apps more capable in the exchange? What’s the likelihood that Apple would do it? Should they?

In this post, I’ve broken down every macOS system app and highlighted where its functionality differs from its iOS sibling, and explored what would need to happen to bring them to functional parity. The assumption being that, if these apps are relatively close to parity already, they might be on the shortlist for Apple to replace with Catalyst à la iTunes. I’m not suggesting that Apple should do this—in fact, quite the opposite, I love Mac-like AppKit apps. I’m simply thinking through what it would look like if Apple wanted to.

With that massive caveat established (so don’t @ me), let’s jump in.

Jump to a section

- iTunes

- Contacts

- Calendar

- Notes

- Reminders

- Safari

- Maps

- Photos

- FaceTime

- Messages

- Books

- App Store

- Finder

- System Preferences

iTunes

This is an obvious one, and not only because it’s reportedly already slated for replacement. iTunes would perhaps be the textbook example of feature bloat (if product managers had such a thing to learn from), having incorporated nearly every new feature and initiative that Apple has applied itself to over the past 16 years. This is partly due to the fact that iTunes has long been Apple’s sole foothold on the Windows platform, and therefore served as its only channel to reach those billions of potential customers before the iPhone and iPad became Goliaths in their own right. But with the maturity of iCloud and iOS devices standing alone, the iTunes era has finally come to an end.

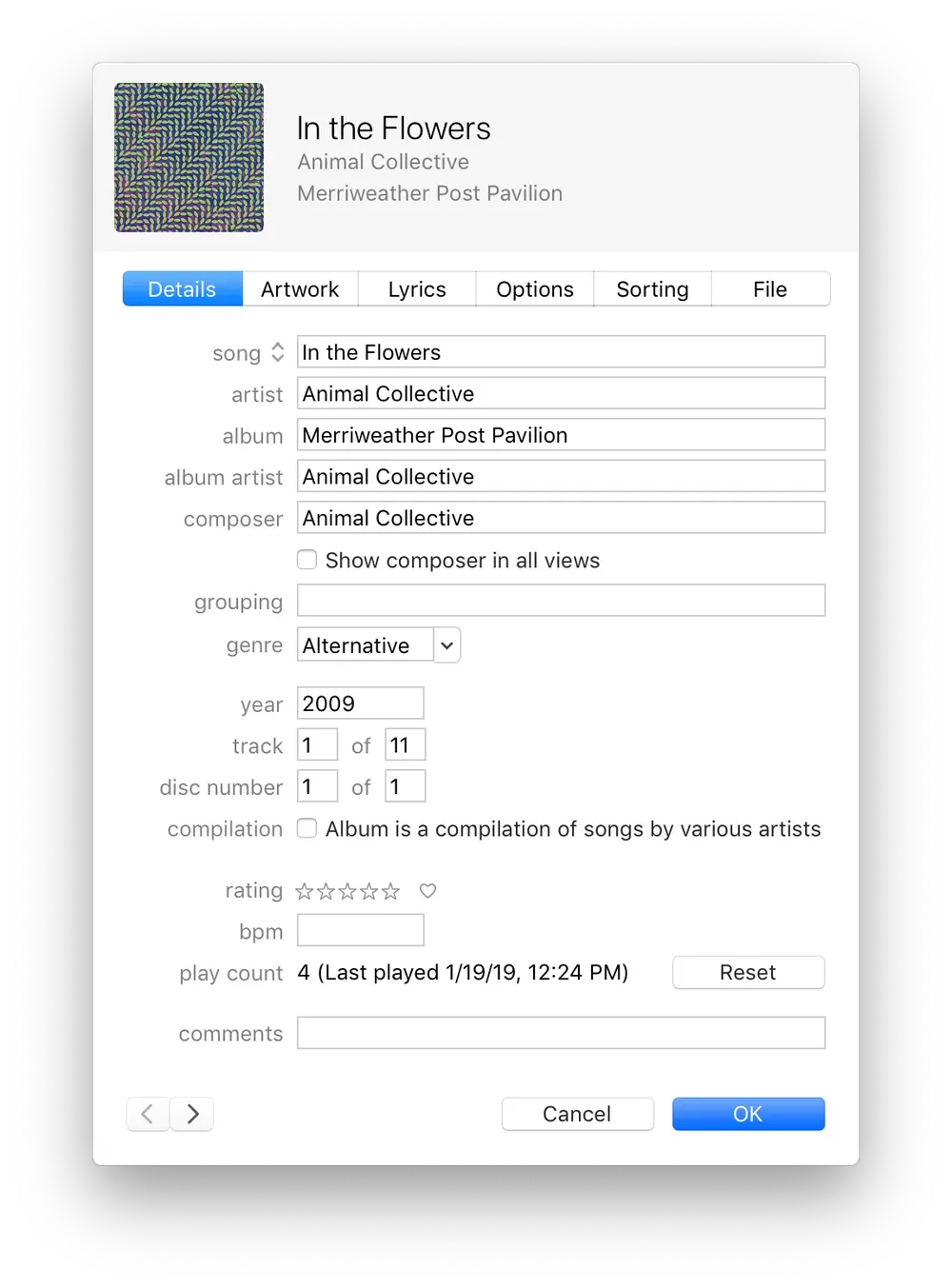

As Macworld pointed out, there are a plethora of more advanced features that make use of the macOS file system to allow power users to manage their music library. The iTunes media folder isn’t a monolithic database that presents to users as a single file like Photos, Photo Booth, or iMovie—it’s a full directory of all their artists, albums, and songs, beckoning them to drag in their high-fidelity files from other sources. Users can manage track and album metadata to add dates, composers, genres, and more, and they can organize tracks within a multi-disc album, add album art, or even manually add lyrics.

Further, users can shop for music on the iTunes Store, something that is still relegated to an awkward purple app on iOS. Given that purchasing and downloading TV shows and movies are blessedly covered by the new Apple TV app, I suspect this is a gap that will be short-lived, and likely glossed over by iOS 13 this summer. But there are also media formats native to iTunes that aren’t yet supported by the Apple Music app, like iTunes LP. (Hopefully, iTunes Extras will be fully supported by the Catalyst TV app.) iTunes also has a bunch of other often-overlooked features from its days as the flagship Apple software product, like internet radio and Home Sharing—not to mention the ability to manage content and operating system updates for every iPod, iPhone, iPad, and Apple TV ever built. It’s a Cronenberg monster of every one of Apple’s Next Big Things™ since 2003.

Where does all this stuff go if Apple Music is ported as a Catalyst app?

Maybe nowhere. Maybe nobody uses these things anymore, and Apple will deploy its headphone jack–killing courage to axe these features, as well. Maybe Apple Music is the future, and we just need to get on board.

But there are other corners of macOS where this kind of cavalier get-with-the-program mentality won’t fly. iTunes is a good example because it clearly demonstrates how the needless complexity of one system can be replaced by something more modern and usable in one fell swoop. But there are other options that aren’t as pretty.

I’ll come right out and say it, Apple Mail is both my favorite and least favorite email client for the Mac at the same time. It’s beautiful, optimized for the Mac, and flexible while remaining simple to use. At the same time, other mail services and clients have completely lapped it in terms of advanced functionality. My kingdom for Mail.app with a Snooze feature.

But this isn’t about Mail versus other clients, it’s about Mail for Mac versus Mail for iOS. They’re pretty similar in terms of design, and for the most part check all the boxes your average email user might demand. But they’re from two completely different decades, and it shows.

Mail for macOS was designed for email as it was in 2002—if not from a technical perspective, then certainly from a user experience perspective. All of your messages are downloaded to your file system, and, in the event you don’t want to synchronize your messages or folders to the server, you can even make use of “On My Mac” folders within Mail like some kind of monster.

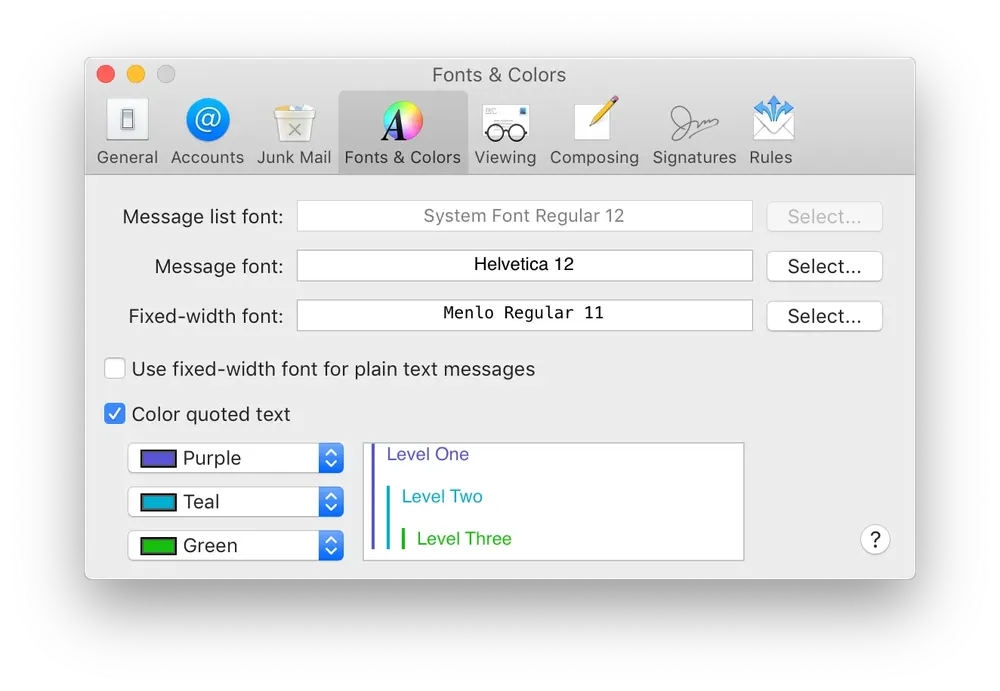

There are also more sophisticated features that power users might still enjoy, but that the everyman hasn’t thought about in decades. These include Rules, which have a lot of utility for those of us who eschew Gmail and can’t make use of its server-side Filter features, and plug-ins, which remain massively important to a lot of folks’ workflows.

Unless the Catalyst version of Mail can support this ecosystem of plug-ins, I simply don’t see this happening. While nothing would make me happier than a special section of the Mac App Store dedicated to Mail plug-ins that work across iOS and macOS, I just don’t see this being a likely scenario.

Contacts

Contacts is different in that its core functionality is already pretty well matched across both platforms. You can create and manage contacts, add fields and photos, or share a contact whether you’re on a Mac, iPad, or iPhone. It’s not going to change the world, but it’s a pretty nifty app.

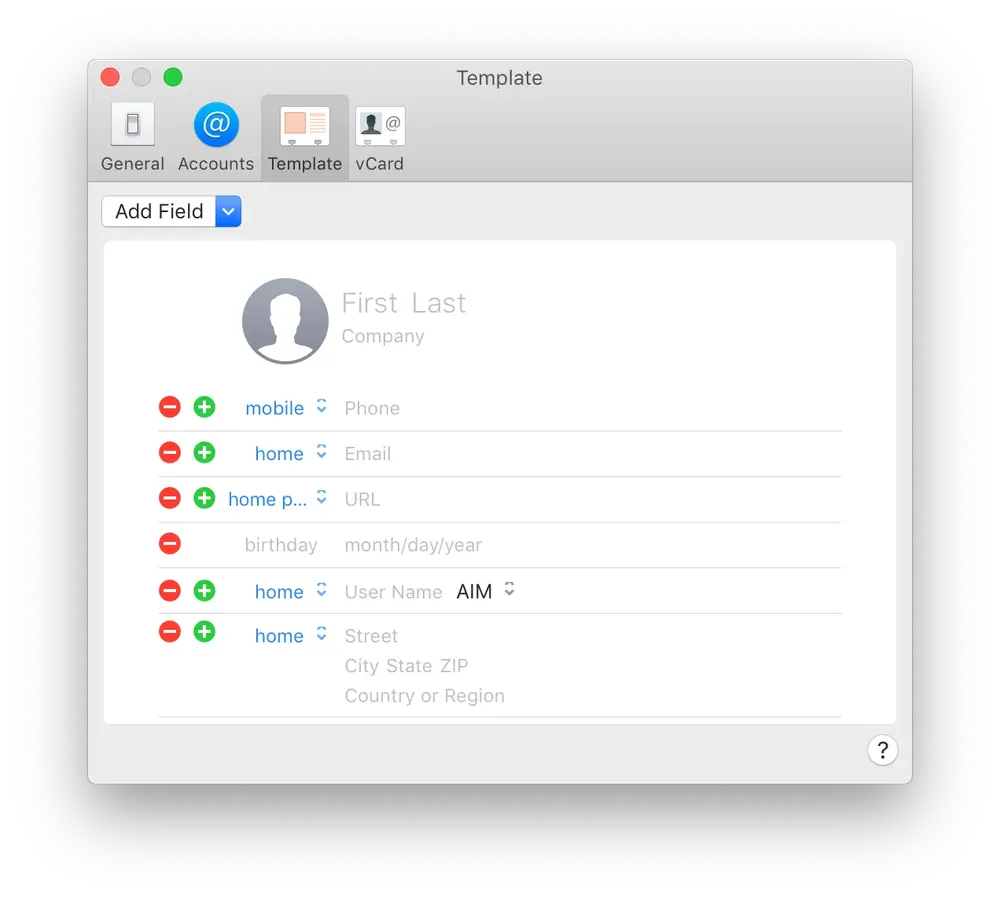

There are a few Mac-specific features, however, that have never made their way to iOS since this app first debuted on iPhone OS 1.0. These include looking for and resolving duplicates, creating, managing, and deleting contact groups, and modifying the vCard template that Contacts uses for new records. You can also opt not to share specific items from your own vCard when sharing it, which isn’t possible on iOS. These things are differences, but they’re not insurmountable, and I really think Contacts might be a likely candidate for UIKit.

Frankly, while Contacts might seem like low-hanging fruit for a Catalyst replacement based on its functional closeness, there’s really no good reason to do it. Nobody’s complaining about Contacts on either platform, and it’s not an area of particular interest for Apple, its customers, or its shareholders. That said, this is a case where adding some more powerful features to the hypothetical shared Catalyst app would benefit iOS disproportionately, so maybe there is a universe where Apple considers this.

Calendar

Like Contacts, this is an area where the two apps are incredibly close, with only a handful of power-user features dividing them. Both apps allow you to create, manage, and delete calendars and events. The more advanced stuff comes in when you begin to consider the various third-party services that Calendar needs to contend with, and where Apple has prioritized delivering the pro-adjacent features that many people rely on.

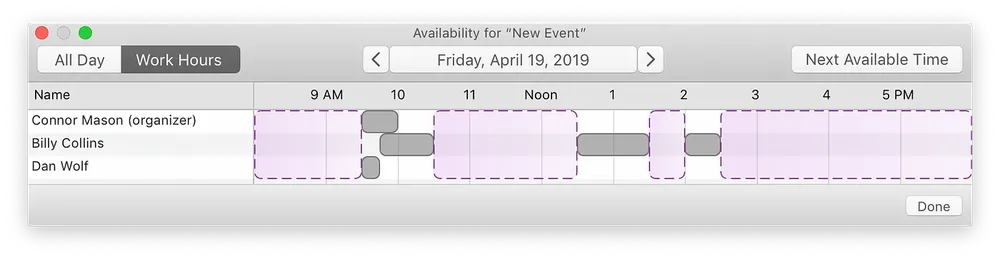

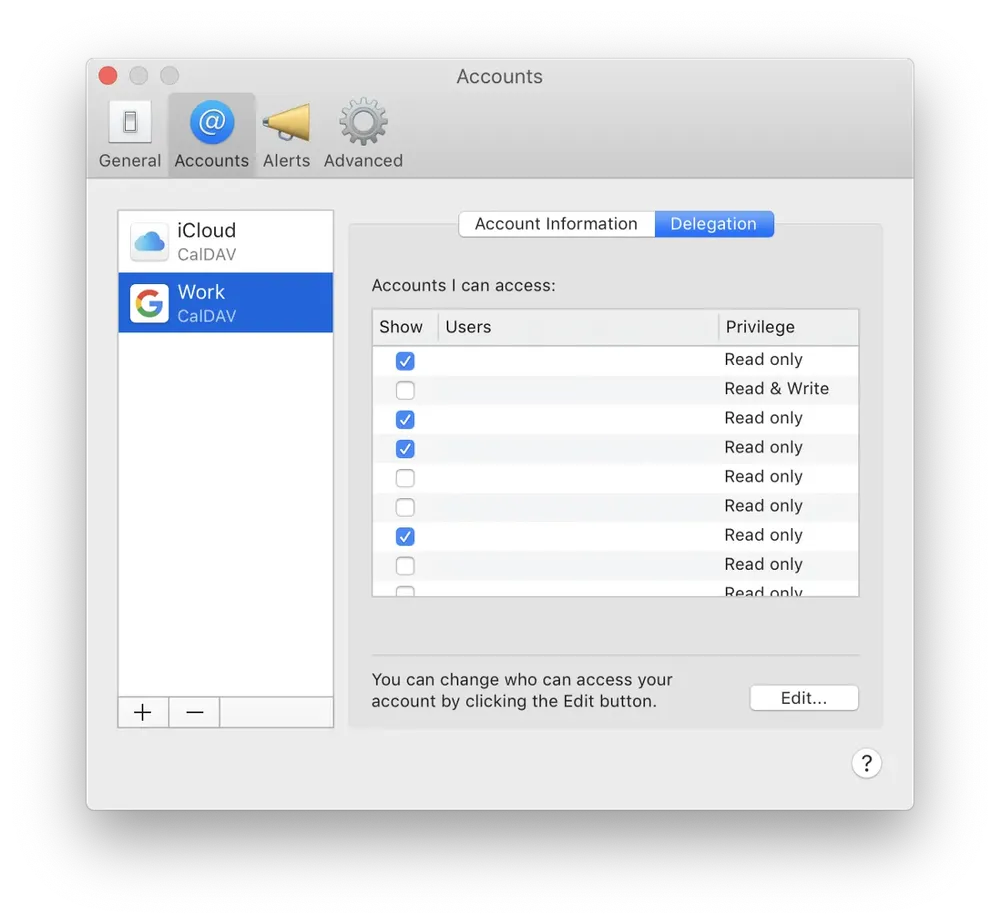

One great example of this disparity is calendar delegation, a feature which allows you to view other users’ calendars within the same interface, and use this information when scheduling meetings with team members within your organization. Outlook and Google Calendars make this a core feature, and it’s incredibly useful on the macOS version of Calendar. Without it, on iOS, scheduling a meeting can become a maddening experience, trying to guess what times of day might work for your colleagues’ schedules and checking to see if they’re free. It’s bad enough that I’ll frequently put down my iPad or iPhone and decide that I’ll schedule the meeting later, if I even need to at all.

Adding this level of support to the iOS version of Calendar would be a win for business users, an audience that Apple is always interested in courting to adopt iOS in the enterprise. More advanced calendar features like these are already common on third-party calendar apps, including Outlook and Google Calendar themselves, so perhaps it’s not an imperative for Apple to address the gap. Maybe like Contacts, this is another example where doing nothing isn’t all that bad. But it would make me sublimely happy.

Notes

Aside from iTunes, this might be the app most likely to benefit from a Catalyst transition. Having once been relegated to living in a corner of the Mail app, its fonts and torn paper serving as more of a showcase for the Apple of that era’s penchant for skeuomorphic nonsense than a useful feature, Notes evolved over time and was ultimately reborn as a powerful Evernote replacement in iOS 9 and OS X El Capitan.

With the importance of iPad’s Apple Pencil features, Notes has seen a lot of attention and iteration over the last few years, and these additions have (for the most part) been brought to both macOS and iOS incarnations of the app. Checklists, links, attachments, photos, password-protected notes, and tables are all available across platforms, and collaboration features in iCloud have made this a go-to note sharing service for many.

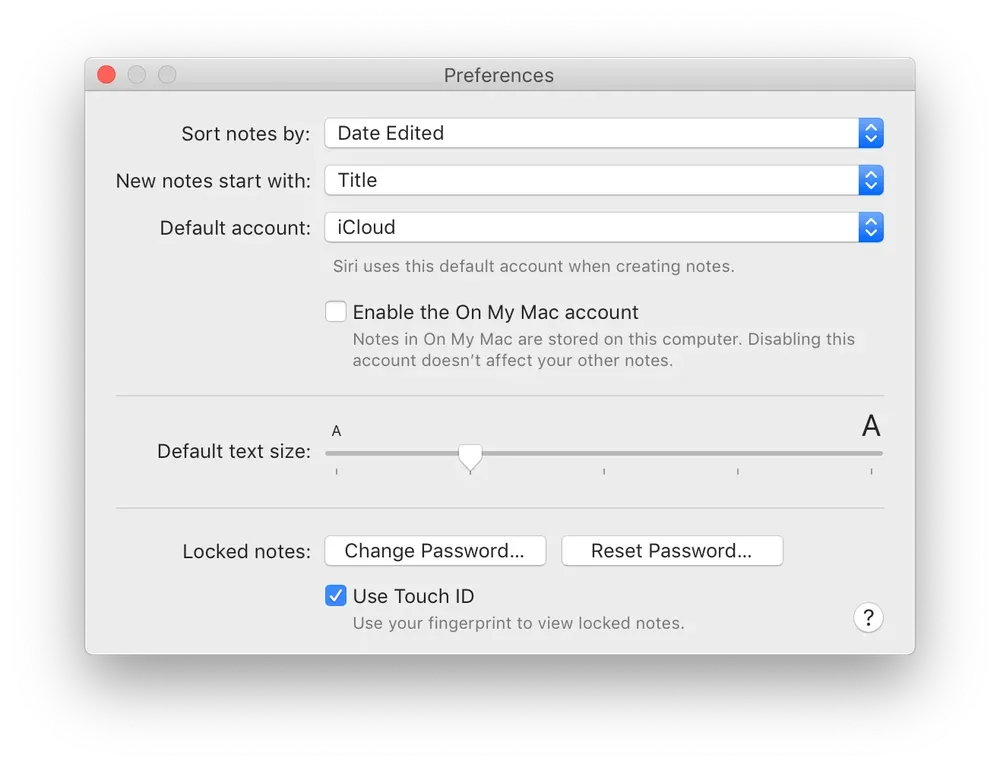

The only feature I’ve found that macOS offers and iOS lacks is nesting folders of notes under other folders. That’s it. (And it might easily be the case that I just can’t figure out how to do it.) Obviously there are iOS-first features, like sketching, handwriting recognition, and document scanning, but many of these are device-specific as it is, and given the context where these features are most useful it wouldn’t be unforgivable if these never came to the Mac. (Although support for Wacom tablets, or Apple Pencil support on a MacBook trackpad, would be pretty amazing.)

My gut tells me that Notes is too important for Apple to risk a subpar experience in the short to medium term, but that the next time they want to add big new features to the service—say, tags, or code blocks, or other cool features “sherlocked” from Bear—they’ll push one new UIKit version and save themselves some time.

Reminders

This app is in dire need of some love from Apple. It’s basically unchanged since it debuted in iOS 5—same out-of-place skeuomorphic design and everything. I suspect they’ll redesign it sometime in the next few years, and the good news is that they’ll likely only need to do this once. There are virtually no differences between the iOS and macOS versions of Reminders that I can discern, save that you can import or export lists of Reminders from the Mac version and can’t on iOS. Like Notes, I’d suspect that the next time something big happens with Reminders, they’ll just rebuild it with Catalyst.

Safari

Full disclosure, I love Safari. It’s fast, capable, and doesn’t spy on me. But unlike some of the others, the difference between Safari on macOS and iOS is completely night and day. I’m not even just talking about developer features (and those are legion), I’m talking about the end user functionality and experience of using Safari across platforms. Despite Steve Jobs’s intonement that iPhone wouldn’t run the “baby web” in 2007, it’s always felt like the iOS version of Safari has lagged dramatically behind its desktop counterpart in terms of the web experience. In truth, it’s not even close, and it’s become comical when the ultra-powerful iPad Pro loads up a mobile-optimized version of popular websites. I’m hopeful that the Safari experience on iPad specifically is a big focus in iOS 13, but I don’t think I’ll hold my breath.

Aside from the state of the web on iOS, Safari for each platform is pretty similar. Both have Reader Mode, Reading List, Private Browsing, iCloud Tabs, iCloud Keychain, Apple Pay, and great new privacy features like Intelligent Tracking Prevention. Check, check, check.

The main differences they do have point to the different use cases that exist for Macs and iOS devices, the differences between the proverbial cars and trucks. Safari for Mac is a download manager, whereas Safari for iOS doesn’t handle more than one file download at a time. Safari for Mac has Web Inspector, and a whole suite of web developer features that I’m not qualified to quantify. There’s simply no comparison.

Safari Extensions are an entire ecosystem unto themselves, and there’s no way we could cover all of that complexity in one Medium post. Granted, these extensions used to be a much more significant part of the Mac user’s experience, and certain tasks like Content Blockers are possible for developers on both platforms, but there’s just too much important difference to preserve there that I can’t see ever coming to iOS. I haven’t even mentioned Safari Plug-Ins yet, and I honestly don’t intend to.

Safari for Mac is a complete powerhouse, whereas Safari for iOS is for simpler workflows by design. We shouldn’t expect this to change, but that won’t stop me wishing.

One exception to this rule are Progressive Web Apps, which Safari for iOS is slowly beginning to take more seriously. Since iPhone OS 1.1 in January 2008, users could add Web Clips to their iPhone’s home screen, a stopgap to satisfy developer interest until the nascent native SDK that would come later that year. After some time, websites could load up a slightly customized UI, abandoning the Safari chrome and adopting a more app-like experience. (I’ve heard a lot of people credit Apple with inventing Progressive Web Apps because of this, which is patently absurd.) More recently, support for Service Workers has meant that these PWAs can have more offline capabilities, and feel more like native apps overall. They’re kind of neat.

For many companies who want to explore other technology stacks, progressive web apps have become the name of the game, and developers like Twitter, Starbucks, and the Financial Times have rethought their web experiences around PWAs. On other platforms like Windows and Chrome OS, users can install these progressive web apps as real apps, and they launch in their own windows with their own colorful app chrome. No part of me ever expects Apple to adopt this for macOS—something like an “Add to Launchpad” button, for instance—but I mention them because this functionality exists in some form on iOS, and I sort of which they would consider it on the Mac.

The idea of a Catalyst version of Safari for macOS isn’t something I can imagine right now, and I think I’ve given the idea enough consideration. If Apple could begin bringing some of the advanced functionality from Safari for Mac to Safari for iOS, I think many among us in the iPad Pro community would rejoice, but there’s only so much that can be incorporated before it compromises the simplicity of the iOS experience.

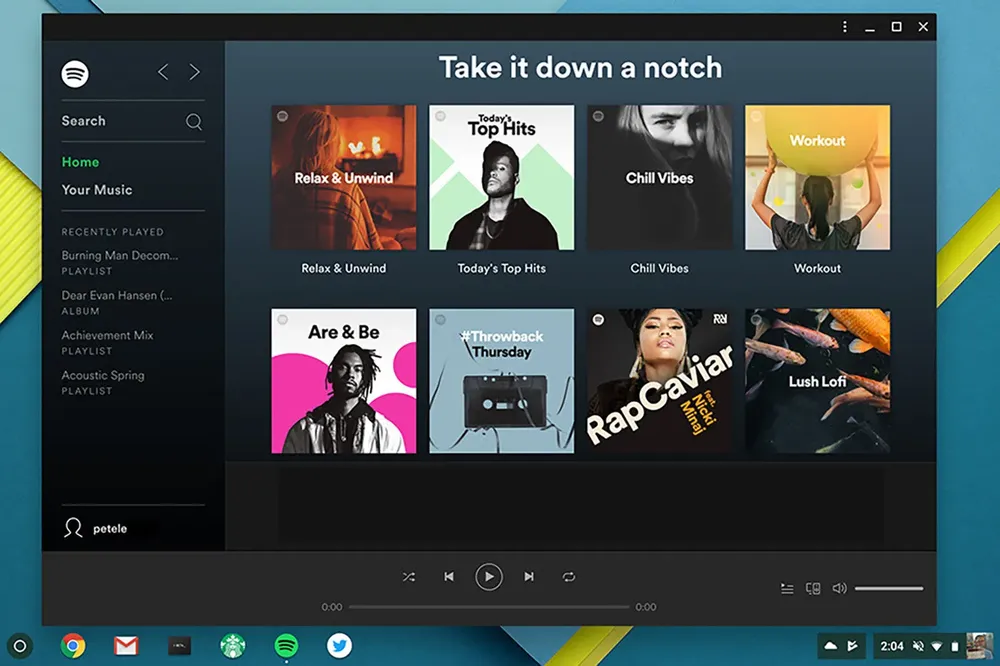

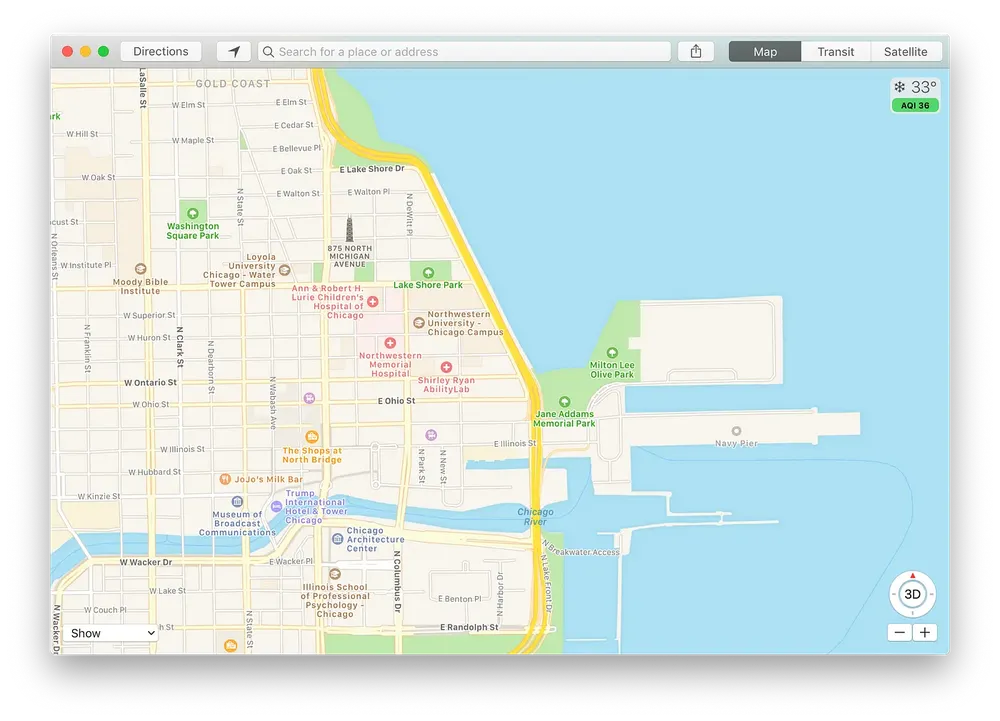

Maps

This one really seems like low-hanging fruit-it already looks and acts like a Catalyst app, and there’s virtually no Mac-exclusive functionality that would be left behind in the exchange. Despite the fact that the Maps app was rumored to be built using the “UXKit” shim that Apple used to build Photos for Mac a few years ago, the iOS app is more up-to-date, more feature-rich, and better designed already, so adapting it for UIKit on the Mac would be great.

Part of me wonders why Apple doesn’t just build a Maps web app using MapKit JS and call it a day—native-specific features like turn-by-turn navigation simply aren’t relevant on the Mac, and they’d gain users from other platforms at the same time. Customers are already accustomed to using Google Maps in their browser, and I doubt many would complain about adding more Maps search results to the search field in Safari. But this is Apple, and native apps are king, so UIKit it is.

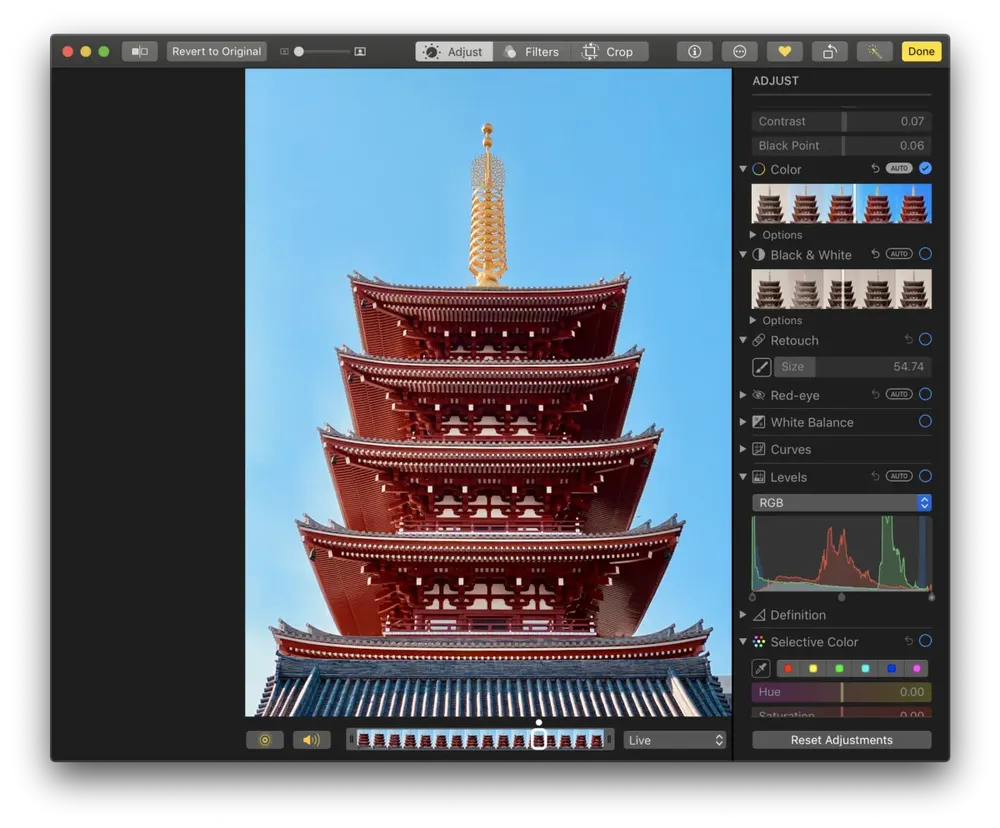

Photos

Photos for Mac has always been kind of an odd duck, in my opinion. Introduced in months after OS X Yosemite’s initial release with the 10.10.3 update and intended to replace both iPhoto and Aperture, it always seemed like a concession versus an app that Apple was really excited about. Fine, we made a new photos app for you Mac people. You can shut up about iPhoto now. No, we don’t know anyone named iLife.

Combine this with the reports that Photos isn’t based solely on AppKit, but rather makes use of a new framework called UXKit that allows Apple to reuse large portions of its iOS codebase for the Mac version, and it begins to look like more of an experiment in cross-platform development technologies than an intentional direction for the product. I’m certainly not the only one who draws connections between what Apple was doing with UXKit in 2014 and what they’re doing with Catalyst today.

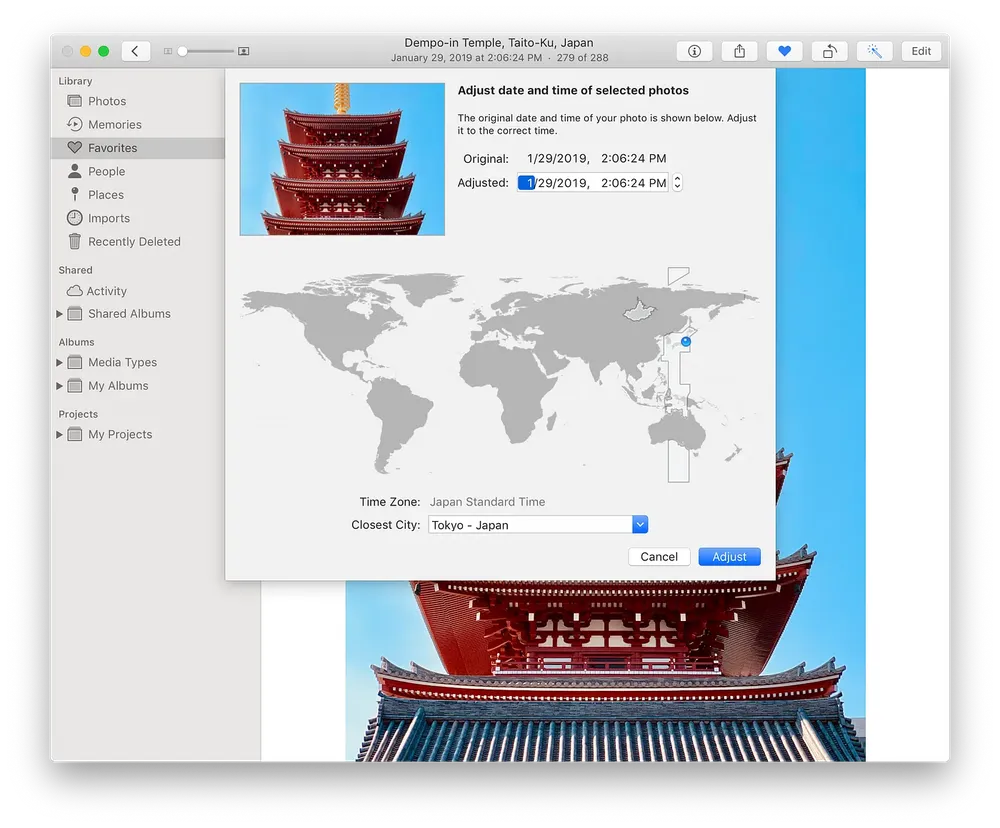

All of that said, Photos for Mac is decidedly more capable and powerful than its iOS forebear. The app inherited all of the comprehensive photo editing and retouching features built into iPhoto, and a handful of the features included with Aperture. Unlike Photos for iOS, you can adjust photo metadata like location, date, and time in Photos for Mac, which would require a third-party app (typically of suspicious quality and revenue model) to achieve the same thing on iOS.

However, perhaps because it seems like Apple already had this objective in mind from the beginning with Photos and their UXKit endeavors, I think it’s pretty likely that Photos is one of the next apps to get the Catalyst treatment. Both Photos for iOS and macOS feature APIs to allow developers to enhance its functionality and add their own editing tools, the Photos Library already exists as a monolithic file inaccessible to novice users (unlike iTunes), and the differences in functionality that do exist are edge cases at best. (However, one example that particularly gets my goat is that you can’t set a “key photo” to serve as the cover of an album from Photos for iOS without reordering the photos in the album. Ugh.) Like Reminders and Notes, I’d bet that the next big Photos feature update also sees a unification of the code around UIKit.

FaceTime

Normally I would have suggested that this would be among the next apps to receive Catalystification (Catalyzation?), but Apple literally just rebuilt this app in Mojave to support Group FaceTime. I suspect that when Face ID and Animojis inevitably make their way to the Mac, and with them the camera effects within FaceTime calls, it might be a good opportunity for Apple to revisit Catalyst for this one. But there’s nothing wrong with it now, so maybe not.

Messages

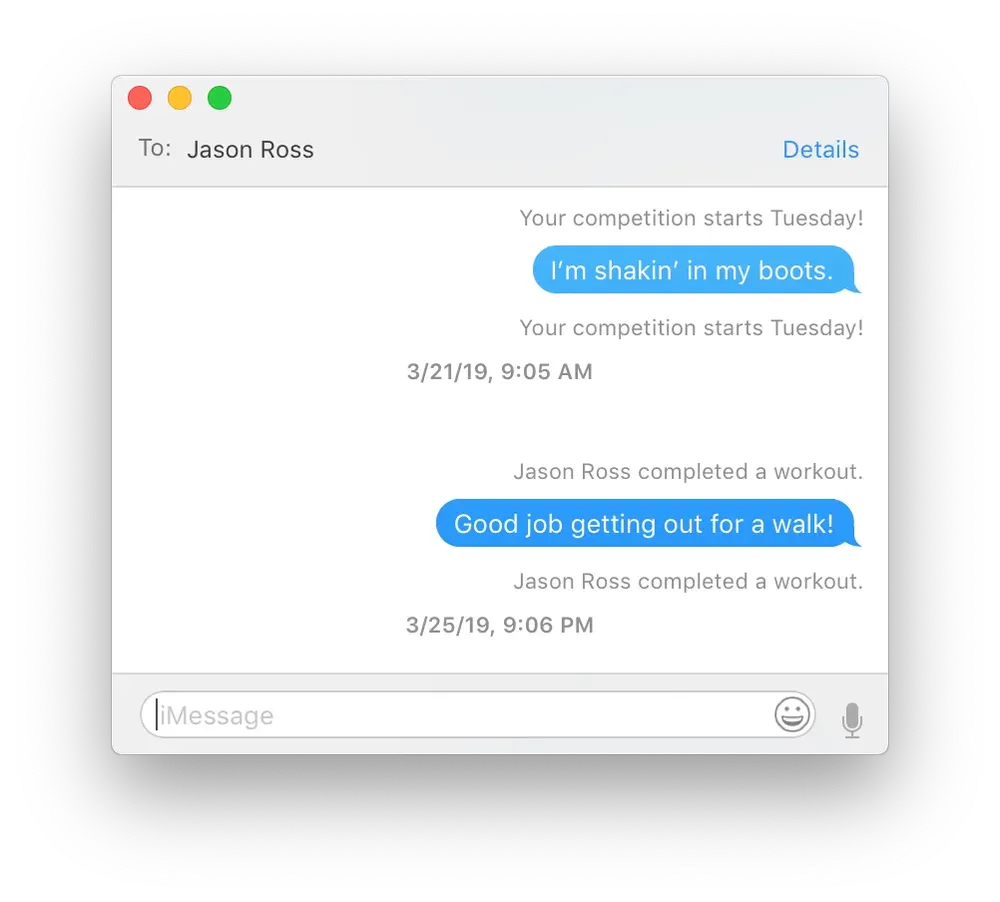

Ooh, boy. This one needs something new. Messages is a fantastic app, don’t get me wrong, but the functional gap between Messages on an iPad and Messages on a Mac is wide enough for iTunes to fit into it. Core features of iOS 10 and 11 like iMessage effects, iMessage apps, and Apple Pay Cash have never made their way to Messages for Mac, and look awkward when they appear within the conversation thread. It’s a disjointed experience, and it’s surprising considering Messages is the number one most used app on iOS.

Unfortunately for Messages for Mac, for years it needed to carry its legacy as iChat into the future, offering support for XMPP and Jabber instant messaging services in an era that had long since left them behind. (I know many people still use Google Hangouts or other Jabber-based chat services, but there are great third-party options for you.) It sometimes boggles the mind to remember that the spiritual precursor to iMessage was support for AIM included with a MobileMe subscription. There are times when the phrase “a simpler time” applies, but this isn’t one of them.

Thankfully for this thought experiment, Apple dropped all of those features from Messages with macOS Mojave last year, so they’re ready to forge ahead with iMessage and SMS forwarding alone. (The app still inexplicably includes the “Buddies” menu in the menu bar, perhaps the only remaining evidence of Messages’ roots.)

I think it’s likely that Messages gets some Catalyst treatment in the coming years, if for no other reason than to achieve feature parity with iOS in the areas mentioned above. There are a handful of things that would need to be carried over—namely screen sharing and multiple windows—but neither of these are show-stoppers, so I think this one is more likely than not.

Books

Apple’s rumored to be replacing the old version of Books in the next release, which will be outstanding. The new version of Apple Books from iOS has great new recommendations, Now Reading features, a Want to Read list, and a much more coherent way to incorporate the Bookstore that feels worlds different than turning the app around to the other side a bookshelf. That said, importing your own ePub and PDF files will need to be handled gracefully, but this one’s already in the Catalyst bag.

App Store

Apple literally just rebuilt the App Store on AppKit last year, replacing the old WebObjects version and matching the curated, content-forward experience that the new App Store for iOS offers. I don’t see them making a change anytime soon, but they might need to if third-party developers will be able to publish their iOS apps to the Mac App Store in a future release of macOS.

Finder

Yeah, this would be a disaster. The Files app for iOS is pretty good, but needs improvement, but comparing Files on iOS to Finder on the Mac would be less like comparing apples to oranges and more like comparing oranges to a Star Destroyer. They’re simply different use cases, similar to Safari, and I don’t see any comfortable way for the two sides to meet in the middle.

Unless. Some part of me has always wondered if Apple will take the Windows RT or macOS Server approach and move the core functionality of Finder out of the main distribution of macOS, making it an optional download for more advanced users. As it is, they obscure the Library folder from Finder to prevent curious eyes from compromising their system, and iCloud Drive tries its damnedest to organize files into simple app-specific folders rather than a complex file system. Would Apple ever ship Files for macOS as the default, offering a straightforward iOS-like experience, with Finder as a supplemental download for the rest of us?

No, probably not. But something like that wouldn’t completely shock me. Maybe they’d strip down or hide the more advanced features of Finder, like when they hid the Library folder or required a command-click and “Open” to get around Gatekeeper. But replace Finder with a UIKit replica? Nope. At least I hope not.

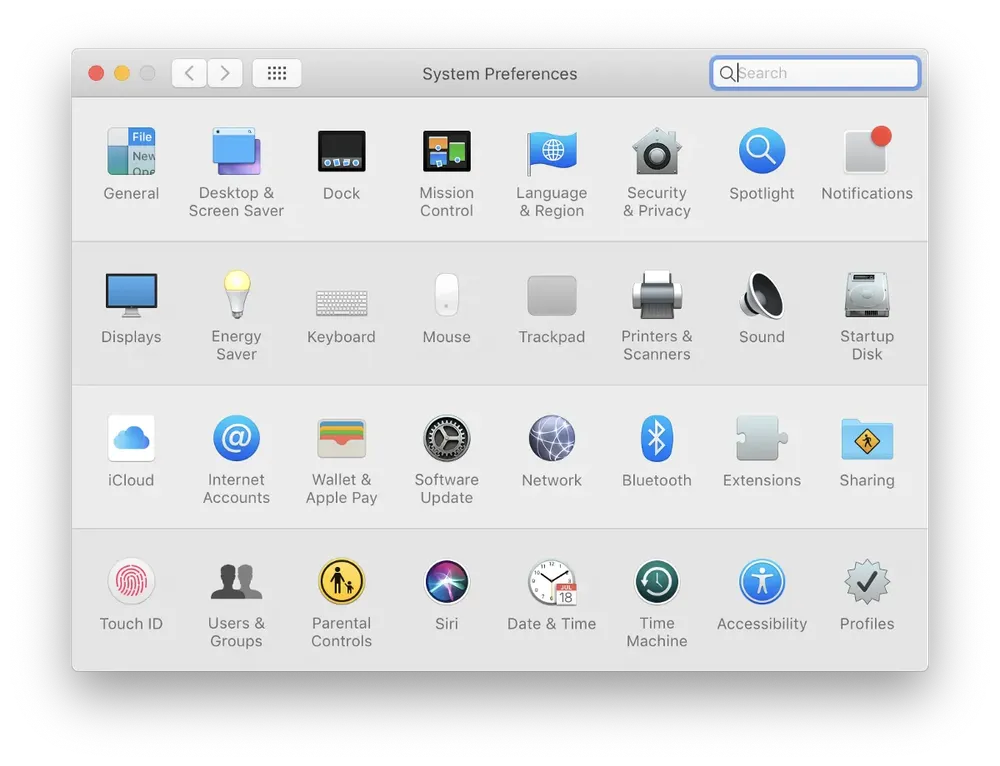

System Preferences

Or is it Settings? This is an interesting one, because the differences between Settings and System Preferences represent two different approaches to the two platforms. On iOS, most app settings were traditionally expected to exist within the centralized Settings app, and all app permissions, like notifications and access to location, are managed there after being granted or denied. On macOS, each app has its own Preferences pane, where accounts can be configured, interface options adjusted, and more. This idea is anathema to iOS, and also wouldn’t particularly translate to the context, given that iOS apps take up the full screen and typically have fewer preference options.

I would love to see some of the properties of the iOS Settings app come to System Preferences, however. For one thing, Settings is much more logically organized for the way people use computing devices today—we don’t think about things in terms of Internet Accounts or Network settings or Sharing settings. These could be nicely reorganized, using an interface and terms familiar to iOS users, and I don’t think too many Mac users would complain.

All in all, I think there are a lot of opportunities for Apple to explore Catalyst as an avenue to modernize its macOS system apps, and I hope it seriously considers some of them. But I think this exercise proves that there are at least a few areas where AppKit will always be a better tool for the job, and until some future framework exists that combines the best of both worlds, I hope Apple leaves some of our favorite apps alone.

Marzipan, or whatever it’s ultimately called, will be most significant in that it could allow hundreds of thousands of great iPhone and iPad apps to run alongside all of these Mac apps on your desktop or laptop, something that would breathe new life into the macOS ecosystem in a revolutionary way. It might not be Apple’s first choice—I don’t think anyone who’s followed Apple for a while would expect them to get excited about a technology that facilitates porting apps across platforms. But hopefully it’s a first step in a process that makes developing for and using Apple’s platforms more consistent, more capable, and more fun.