Responsive versus adaptive web design

As new and more diverse device types have proliferated in recent years, the notion of developing a consistent brand experience for the web might seem overwhelming. While challenges for web development were once limited to compatibility with Internet Explorer, modern web developers need to accommodate a wealth of mobile operating systems, browser capabilities, and screen dimensions. What’s worse, the subtle differences between these devices is getting blurrier and blurrier, as tablets approach feature parity with desktop browsers and mobile phones continue to increase in size. As the web and mobile have both matured, developers have approached this problem in a number of ways. While these methods differ wildly in their technological implementation, they all share a common goal—creating a web experience that feels optimized for every device.

The server does the work: adaptive web design

The iPhone—and, later, all iOS and Android devices—offered users the “full” web in a way they’d never experienced before on a mobile device. Rather than serving a watered-down version of webpages that Steve Jobs called the “baby internet” in his 2007 keynote presentation, the iPhone’s Safari web browser could render full HTML and CSS on a 3-inch screen. Thanks to multitouch panning and zooming, full desktop websites were not only accessible on a mobile screen, but also navigable.

The web had changed overnight—web developers now had to consider how their desktop web designs looked and worked on mobile, and how their forms and buttons played with users’ clumsy fingertips. As mobile exploded in popularity and mobile web traffic became increasingly large percentages of websites’ overall visitors, developers looked for ways to deliver a favorable web experience to visitors regardless of their device. Much of the web’s video was delivered to desktop via Adobe Flash, which wasn’t supported on iOS and presented performance obstacles on the few Android devices which briefly supported it. Designers had to accommodate often-suboptimal connection speeds over 3G networks, which meant trimming features and minifying code to serve leaner websites more quickly and efficiently.

But what if developers could create an experience that was perfect for desktop, using desktop-specific code and fully-realized features, while also offering a mobile experience that took into account the priorities of mobile browsers and addressed the needs of mobile users? Web servers could deliver device-specific content based on the web browser’s user agent, which identifies the device type, operating system, and browser capabilities. Web developers could offer two or more versions of their websites, each built with a different device category in mind, and the web server would intelligently serve the appropriate site files to deliver the best possible experience for that unique device. This approach is called adaptive web design, and is popular with major websites in industries as diverse as web publishing and online banking.

Websites that follow the URL design pattern mobile.example.com or m.example.com are using the adaptive web design technique, but the URL doesn’t necessarily have to change between devices. While effective at delivering a consistently optimized web experience between devices, adaptive sites run the risk of redirecting users to nonexistent pages if developers and content creators aren’t careful—certain pages might be made to exist on the mobile site that are accidentally inaccessible from the desktop site, which could deliver 404 errors and cause user confusion between devices. Web developer diligence is required to concurrently update two distinct code bases and ensure that no users are redirected to empty pages.

The browser does the work: responsive web design

Simultaneous updating of distinct desktop and mobile code bases seems a small price to pay for consistent optimization between devices, and adaptive design makes sense for many companies whose users have differing needs on different platforms. But for many companies, building one website that seamlessly supports any screen size and resolution offers a cleaner, more future-proof solution that still adapts to users’ devices and still delivers an optimized experience everywhere. These websites could adjust their designs on the fly, changing font sizes and image widths dynamically as users’ screen sizes—or even the width of their browser windows—change. This is responsive web design, and it seems like the web design holy grail.

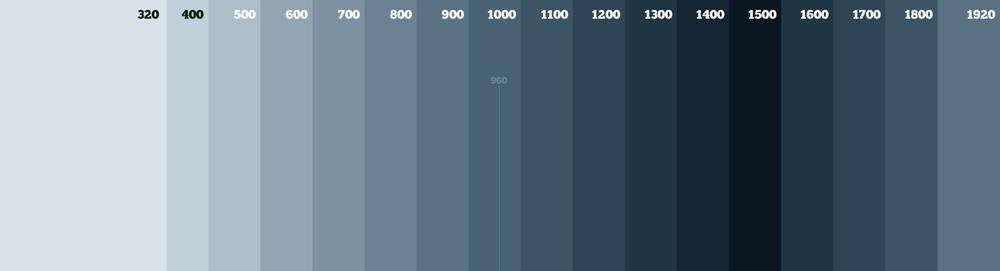

Responsive websites use CSS modules called media queries to determine a user’s viewport size, after the website code has been downloaded to the user’s device. These media queries can then add or remove CSS rules to the site’s design, allowing the website to rearrange and resize its elements to accommodate different breakpoints—various screen widths that represent mobile, tablet, or desktop resolutions. While a responsive site’s CSS is slightly more cumbersome than that of a site designed exclusively for desktop or mobile, this unification means that web developers only have one code base to maintain, and eliminates any possible content-mirroring issues presented by adaptive sites. These instant design adjustments occur all in the code already loaded into the web browser, meaning users can watch these calculations and determine breakpoints in real time.

Wondering if a site is responsive? If you’re on a desktop or laptop with browser windows, resize the Punchkick website view now by grabbing the corner of your window with your cursor. Because our website is fully responsive, you can watch as content rearranges itself into different view sizes.

Responsive web design can be elegant, but certainly needs more design considerations upfront to ensure its success. Because of its immense popularity in recent years, web designers have developed a number of responsive frameworks that can fast-track responsive web development, including Bootstrap and HTML5 Boilerplate. Since they don’t make assumptions about what constitutes a “desktop” or “mobile” screen size, responsively designed websites are relatively future-proof—an important consideration for ever-growing Android phone screens and as Apple gears up to announce its rumored 4.7-inch and 5.5-inch iPhones. And, perhaps best of all, responsive websites are very search engine friendly—Google itself recommends responsive design for websites whose content needs to attract search traffic, as having one responsive website is preferable for SEO to a site with two distinct versions and possible redirects.

But which one works for me?

There’s no simple answer to whether adaptive or responsive design is better for a company’s website—it’s entirely a case-by-case situation. For certain brands, serving universal web content with a strong SEO footprint is key. For others, there are considerations about mobile use cases that might make adaptive design a better option. But in the interest of prescribing a rule of thumb, web developers have reached a general consensus—unless your website has a specific reason to deliver unique features to mobile users, it’s better to go responsive.

However, this shouldn’t imply that responsive is necessarily a better option—there are plenty of specific reasons why adaptive design could be more appropriate. The explanation comes down to understanding users’ priorities on desktop and mobile web. For mobile banking companies, mobile users might be interested in making quick transfers or checking account balances, while desktop users might need access to more in-depth documentation of their transaction histories. Desktop readers on news websites might be interested in viewing comment threads on a new article, whereas mobile users might be solely invested in the content itself. There are many reasons to consider adaptive design, but they all come down to addressing unique user needs on different devices.

But that doesn’t mean that mobile sites should only address the concerns of the majority mobile user—there are use cases when transaction details and comments make sense for mobile, too. The key is finding a balance between immediate utility and discoverability, hiding more advanced or infrequently-used options but leaving every feature available. Users come to mobile websites with certain expectations, usually informed by their experiences on the desktop site. For this reason, mobile web best practices suggest feature parity with the full desktop site on both responsive and adaptive sites, even if certain options are tucked away in menus or toolbars. As long as common actions are available in every version of the site, and as long as actions uniquely relevant to certain devices are prioritized where necessary, users win.

In the end, it matters less how brands adjust their website to accommodate mobile users, and more that they make these considerations at all. As mobile web traffic continues to grow exponentially, and as more international internet users begin adopting smartphones as their first and only internet-enabled device, brands should begin valuing their mobile web experiences as many customers’ only gateway to their products or services. And, since Google has gone so far as to begin favoring mobile-friendly sites in its search results, considering the mobile web is nothing short of imperative for brands looking to be discovered on the web. Regardless of the approach, developing web experiences optimized for both desktop and mobile is a guaranteed way to drive engagement across devices and begin to make a brand impact on mobile.