Google redesigns Android, one app at a time

Android everywhere

This post is excerpted from the Android everywhere series.

Even before its release in 2008, Android’s only constant has been reinvention. What began as a basic operating system for feature phones has exploded into the top mobile platform on the planet, with the industry’s largest touch screens and most extreme hardware capabilities. Android became a diverse and robust ecosystem of smartphones and tablets, with custom designs and features for each distinct manufacturer. The core of Android remained strong, but its influence was waning: as Google iterated its platform with new features and versions, carriers and OEM partners were sloth to adopt. When Google looked to expand Android onto types of devices—like wearables, televisions, and cars—it came time to pull the reins harder.

Android Lollipop represents Google asserting control of its platform, and its intention to bring its singular vision for Android to every connected device in your life. Welcome to Android everywhere.

The growth of Android’s market share foothold, at least within the United States, stemmed in part from a fruitful yet complicated partnership between Google, Motorola, and Verizon. Having acquired rights to the name “Droid” from Lucasfilm, the companies developed and aggressively marketed a series of handsets named after the robots of Star Wars fame. The Motorola Droid and its successors positioned Android has a powerful yet approachable mobile operating system, and the companies’ marketing fully embraced the powerful and technical nature of Google’s software. But each company began to make compromises. As Verizon asserted its control over within an exclusive contract, the carrier began to define which apps and services shipped with Motorola’s handsets. As the Chicago-based manufacturer built out a larger family of Droid products, Motorola started tweaking the user interface to differentiate its Android smartphones from competitors like HTC and Samsung. As non-Google partners started toying with its open and adaptable operating system, the core Android message became lost among the posturing.

Motorola wasn’t the only manufacturer altering the Android user interface. In addition to Moto Blur—Motorola’s in-house Android skin that added social utilities and a redesigned app launcher—Samsung tweaked Android with its TouchWiz and HTC with its Sense UI. These custom skins added some welcome functionality on top of Android, but typically came at the cost of performance and speed. More importantly to Google, it began losing control of its platform’s strong message. Rather than “Android phones,” these handsets were becoming identified by their manufacturers’ interpretations and modifications before all else. Users reported owning “Droids” or “Galaxies,” not Android phones. Part of the issue came down to marketing messaging, which could be amended. But Google had a larger challenge ahead of it, another fallout from its dependence on carrier and manufacturer partners: fragmentation.

As Apple routinely drove updates to its iOS software to iPhone and iPad users over the air, Android was frequently stuck in neutral. Because carriers and OEM partners could determine for themselves when their phones received Android system updates—or, if they received them at all—many users continued running 2.3 Froyo for years after 4.0 Ice Cream Sandwich became available. Manufacturers worked to update their custom interface skins to be compatible with new Android versions, but this development lead-time often took months or more after Google first unveiled the platform’s next iteration. Fragmentation became a real problem for Android, and severely impacted not only Google’s ability to innovate, but also developers’ ability to feasibly design their apps to run on a majority of Android handsets. Google had lost control of its platform, and was beholden in many ways to its partners to ensure adoption.

To amend this in the short term, Google began releasing its popular Nexus line of smartphones and tablets, built alongside manufacturing partners and designed to run the latest and greatest versions of Android. Nexus phones received over-the-air Android version updates as soon as they became available, and remained completely under Google’s control in terms of capabilities and software compatibility. Nexus devices offered a solution to fragmentation for consumers buying new hardware, and allowed Android fans to take advantage of the shiny new things announced at every Google I/O developer conference. Google even expanded this approach to the Google Play Edition program, which offered manufacturing partners’ flagship devices—like the Samsung Galaxy S5 or HTC One—running “stock Android” at an “unlocked” premium price on the Google Play Store. But Nexus and Google Play Editions weren’t a solution to Android’s fragmentation ills for all Android-kind, and simply represented a proverbial “city on a hill” for OEM partners to aspire to. The wider Android ecosystem remained outside of Google’s direct control, and its users couldn’t take advantage of the platform’s latest features. Thankfully, Google itself had already developed an escape hatch: the Google Play Store.

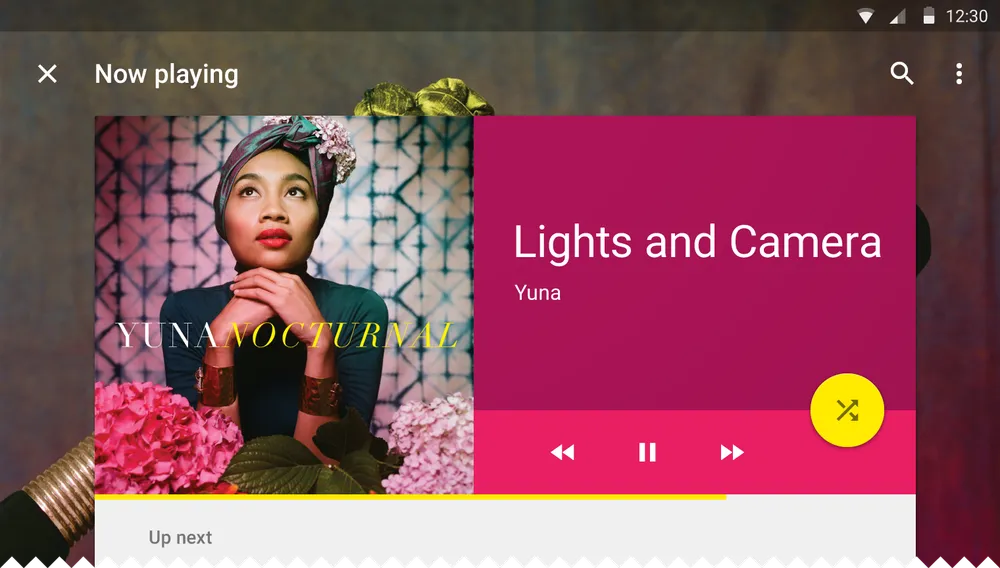

Through the Google Play Store, Google could push updates to core apps and services without requiring users to first perform system updates. Apps like Gmail, Hangouts, and more could run on older OS versions without incident, allowing Google to push its latest design aesthetic and ideas to as wide a range of customers as possible. When Google began rolling out the first updates for Material Design this fall, even users on 4.4 KitKat and above could take advantage. Google Calendar, Gmail, and Hangouts all saw Material Design updates in the Google Play store weeks before Android 5.0 Lollipop was released, allowing users on older and non-Nexus handsets to adopt the company’s new design philosophy immediately. Unlike Apple and iOS, users didn’t need to upgrade an entire version number just to use a hot new feature in Mail. If Google wanted to remain sole steward of its platform, it needed to reach even the furthest among its flock—and the independent app update strategy allowed Google to infect older phones with its design aesthetic one app at a time, adding Material interfaces to core products without needing a system-wide Lollipop overhaul. In short, it solved for fragmentation: while Android’s user base lagged behind on version updates due to tedious partner holdups, Google could forge ahead into new territory and cast a shadow of designs and features backward to the outdated masses.

App updates are time travelers

Earlier this fall, Google unveiled an all-new take on its Calendar app for Android. Strongly infused with Material Design ideas and built to better incapsulate various areas of users’ lives, the new Calendar replaced the outmoded Google and stock Android Calendar apps for millions of Android users. But its timing was indicative of a new Google product rollout strategy: it came weeks before public availability of Android 5.0 Lollipop, the operating system update whose design cues it borrowed. And it was designed to run on 4.4 KitKat and previous versions, meaning a huge portion of Android’s install base across a myriad sampling of devices could upgrade immediately. The move was intended to improve the Android calendar management experience for as many users as possible, and worked within Google’s frustratingly fragmented software ecosystem to do it. But Google Calendar wasn’t a one-off example: Google began aggressively expanding its Material Design revamp to a wider selection of core Android apps. And because of its app-centric update strategy, even users running past Android versions would benefit.

In fact, Material Design informed the direction for a brand new initiative from Google’s Gmail team. Having acquired the talent behind a novel take on Gmail management called Sparrow, the company spent years of research and product development on a new approach to Gmail inbox management. Borrowing liberally from inbox triage products like Mailbox on mobile, Google Inbox applies task management philosophies within a Material Design framework. Organizing messages into intelligent “bundles” and allowing users to snooze conversations for later, Inbox builds upon a foundational Google service and reimagines it for Material Design. Expanding and transforming Gmail’s primary feature set, Inbox represents a Material Design remake of Google’s most popular and broad-ranging product. Google knows that design isn’t just what it looks like, and Inbox redefines how email works within a Material Design context. But Google wasn’t replacing the venerable Gmail—it was just getting started.

The longstanding Gmail Android client was next, adopting a red accent color and material elements from the company’s comprehensive guidelines. Most interestingly about Gmail was its surprise inclusion of POP and IMAP support, allowing users to add non-Gmail email accounts to the app and receive their Outlook or Yahoo messages in parallel. This move suggests that the Gmail app is intended to replace Android’s longstanding email client for third-party mail services, and could grow to encompass Exchange and other email server types in coming versions. Google was moving to replace core Android system services—calendar management, email clients, and more—with Google-specific application products like Calendar and Gmail. For many, this approach has been polarizing: whereas previous versions of Android have seen new versions of apps fully open and adaptable to any company’s varying intention, recent incarnations have seen little improvement to those underlying apps in favor of shiny new renditions of Google’s core product family.

“Google has Gmail, Calendar, Google Camera—all these were core components of the Android operating system—and they’ve turned them into Google-branded apps. They’re turning core components of the OS into ‘apps,’ which can be independently updated.”

Of course, Android still exists as an operating system that manufacturing partners can iterate and remix. HTC, Samsung, and others have built their own custom interfaces and apps on top of the core Android layer. But Google’s stock offering—the variant of Android that ships with Nexus products and is available from Google’s developer website—is overcome with Google-specific applications. Of course, this approach makes business sense: Android is free, Google services are free, and a wider user base allows Google to show more advertisements and monetize its cloud service creations. Google Chrome is perhaps the quintessential example: the Android browser lives on, largely unaltered since its Holo-style redesign under Ice Cream Sandwich. But Chrome, meanwhile, has been reinvented with Material Design and takes advantage of new Lollipop-specific features, like separating tabs into distinct cards in 5.0’s multitasking views. This strategy is neither good nor bad for Android—rather, it tweaks Android’s perception as an open-source project and solidifies Google’s investment in the platform as a product. Android is perhaps the largest smash-hit in the history mobile industry, and Google is rightfully staking its claim.

Material everywhere

Material Design isn’t just for the next generation of Gmail or Chrome—it’s intended for every app across platforms to build interfaces that play nicely with their environments. Whether on Android, Chrome OS, or on the web within Chrome, Material Design apps and websites will adopt a consistent style and predictable behavior that spans screens and form factors. But a system with such uniformity might suggest that third-party app designers’ hands are tied, and that future versions of popular Google Play apps will begin looking identical. On the contrary: Material Design not only allows for a wide degree of customization and individuality, but also offers a real opportunity for developers and designers to quickly and efficiently build modern Android apps that reach an unprecedented number of users.

The design prescriptions in Google’s Material Design guidelines are specific, but not constraining enough so as to limit designers’ creativity and stifle brand uniqueness. Apps like Facebook or Twitter can incorporate elements of their unique design aesthetics while maintaining compatibility with Material Design as an ideal. Overly strict adherence to any design philosophy can imply destructive uniformity and standardization, but designers have elbow room within Material Design. The guidelines prescribe shapes, interface architectures, and even a palette of colors to help apps feel at home on the Android devices they populate. But the suggestions and guidelines around logical layering and animation best practices are basic learnings commonly known among interface designers.

“Material Design is appropriately named, because it’s not called ‘Android Guidelines.’ It’s material guidelines. Google is providing you with subtle user interface cues that you can choose to tap into, like color usage and animations. It does give you colors to work with, and guidance on how those colors work best in the foreground or the background—basic ‘Design 101’ stuff that you can insert your brand into.”

Not only is Material Design compatible with brand standards across a myriad of industries, but it also might be beneficial for brand designers to explore. Because compliance and modern design practices go a long way to inspire user trust, adopting Material Design components can help brand designers capitalize on the operating system’s new look and encourage users to feel comfortable with their apps. “If I download a Chase app onto my Android phone, and it references some of the nicer aspects of the platform, like the animations and the subtle cues for depth, it helps me feel like it belongs on my phone,” Detskas explains. “The polish helps me trust it. So if a solid design engenders trust, it’s in a company’s best interest to leverage those guidelines wherever they don’t conflict with their brand.”

Like Google, third-party Android developers can take advantage of backwards-compatibility though Google Play Services. As Google fights fragmentation by opening new APIs and features to older versions of Android, developers have new opportunities to reach ever larger audiences of Android users. As Material Design works its way backwards and crops up on older devices and among older interface techniques, developers can modernize their apps with greater agility and still maintain a level of consistency. Google has made strides against not only Android version fragmentation, but also interface design fragmentation brought on by disparate interface strategies and customizations by Android hardware manufacturers. Gmail, updated with Material Design, runs the same on multiple years’ worth of Android versions and on interface skins maintained by HTC, Samsung, Motorola, and others. Third parties, too, can begin shipping consistently designed apps across versions and interface modifications.

“These different Android skins impact development. Sometimes, standardization can be a good thing for developers, because that’s less variance that you have to account for. That kind of segmentation is where bugs start to occur, because developers can’t account for that wide variance. When Google standardizes, the development target becomes a lot smaller.”

Material Design is only part of Google’s play to tackle fragmentation, easily the largest issue facing its leading platform from developers’ perspective. Google is simplifying the Android development process—both by standardizing design aesthetics and by minimizing the number of Android flavors that require distinct versions of third-party apps—which will attract another class of developers. With Android, Google cast a wide net to achieve unprecedented market adoption—but in so doing, made concessions to carriers and manufacturers on design and upgradability that have crippled some aspects of the platform. Now, with Material Design updates assisted by Google Play Services, Google has begun standardizing its platform and aligning its billion-plus customers to be ready for what’s next. And what’s next will fundamentally alter how customers perceive Android and define the platform’s trajectory into the next decade.